Nicholas Ferrar was the son of a London merchant who was an early member of the Virginia Company, the group which established the American colony in 1607. In 1622 Nicholas succeeded his elder brother John as the company’s Deputy, becoming responsible for its day-to-day administration. In 1624 twin disasters struck; the company was dissolved and John faced a threat of bankruptcy. This turn of events convinced Nicholas and the family that they should renounce worldliness by leaving London and devoting themselves to a life of godliness. Nicholas and John’s widowed mother, Mary, purchased the manor of Little Gidding as part of a deal to rescue John from debt. An outbreak of plague in London in 1625 caused the family to move to Little Gidding more promptly than they had intended. On arrival they found the church used as a barn and the house, uninhabited for 60 years, in need of extensive repair.

Establishment of a community

Old Mrs. Ferrar’s first action was to enter the church for prayer, ordering it to be cleaned and restored before any attention was paid to the house. Mrs. Ferrar’s daughter Susanna, with her husband John Collet and their many children soon joined the household from Bourne in Cambridgeshire. The household numbered about 40 persons from babies to septuagenarian Mary. A school was established for the children of kinsmen and friends as well as family though not for the local children, who were offered a copy of the psalter from which they could learn the psalms. One wing of the house became an almshouse for four elderly and infirm women. A dispensary was set up in the house to provide broth and medicines to the local people.

Establishment of a regular round of prayer

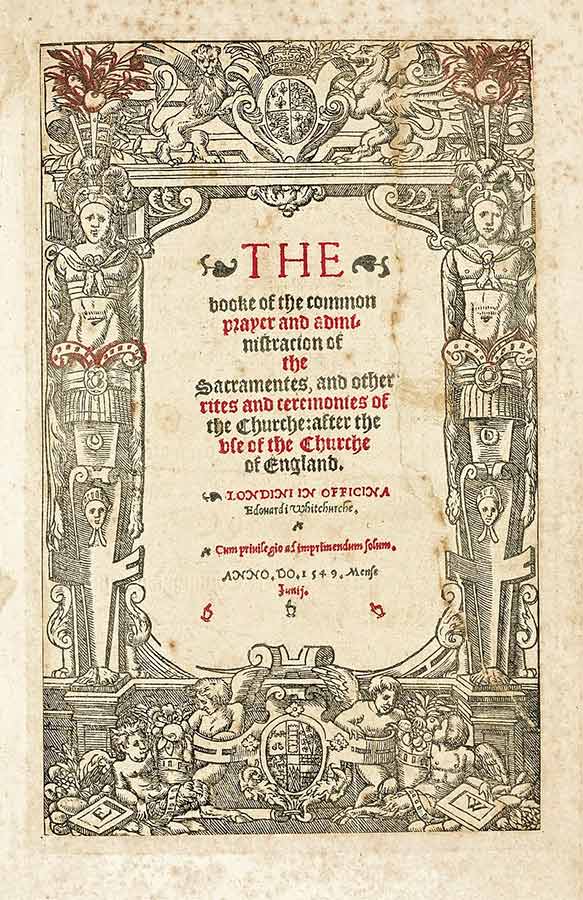

The title page of the 1549 Book of Common Prayer

In 1626 William Laud, then Bishop of St. David’s but later Archbishop of Canterbury, ordained Nicholas a deacon though Nicholas made clear that he would not proceed to the priesthood. He and the family soon established on weekdays a regular round of prayer based on Archbishop Cranmer’s Book of Common Prayer. The family processed to the church for these services of matins, the litany, and evensong, which were led by Nicholas. On Sundays Nicholas led the customary matins to which the local children came and afterwards recited the psalms they had learned, for each of which they received a penny. After the recitations were completed, all returned to the church where the Vicar of Great Gidding (Little Gidding’s rector being an absentee) led another service that included a sermon and, once a month, Holy Communion. The psalm children then went back with the family to the house where the family, including old Mrs. Ferrar herself, helped to serve them lunch. When the family had in turn finished their lunch, they walked over the fields to Steeple Gidding for evensong.

Nicholas also began a round of hourly devotions in the house that combined recitation of psalms and readings from the gospels led by members of the family. These were later augmented by nightly vigils in which participants again repeated the psalms.

Gospel harmonies

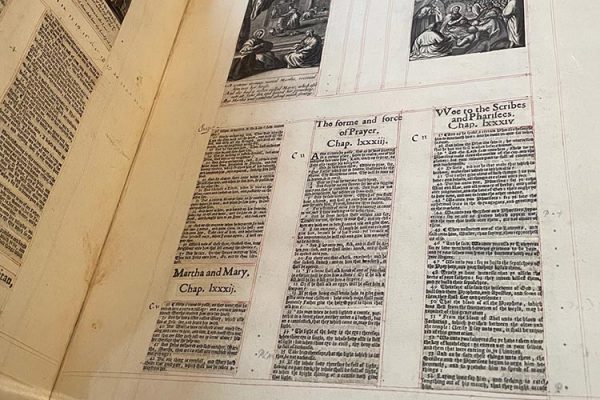

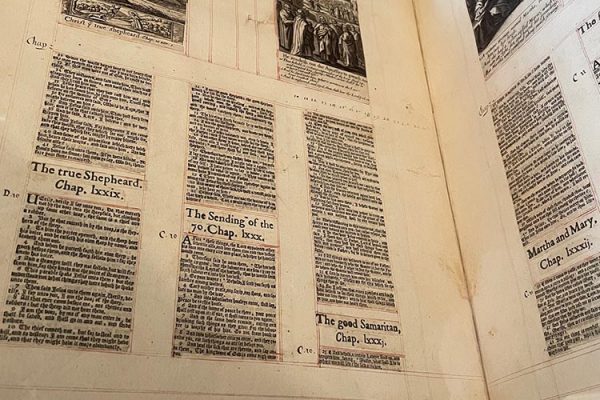

To instruct the younger members of the extended family in the gospel story and to develop their manual dexterity, Nicholas devised a Harmony of the four gospels. This Harmony provided the narrative for the hourly gospel readings. To create it, individual lines were cut from the four gospel narratives and pasted together on the page to make one continuous text. The pages were also illustrated with engravings, some of which Nicholas may have brought back from his continental travels many years earlier.

When King Charles heard of the Harmony’s existence, he sent to borrow it, returning it only when the family agreed to make another for him. The family also made others for absent family and friends as well as for other royals and members of the nobility. The poet George Herbert, who received one, returned the family his thanks that ‘he had lived now to see women’s scissors brought to so rare a use as to serve at God’s altar.’ Fifteen such volumes are known to survive, four of them in the British Library.

Pages from a Gospel Harmony, made by the women in the family, now at Ickworth House Suffolk.

Death of Nicholas

In the autumn of 1637 Nicholas sickened, dying on the day after Advent Sunday at 1 am, the hour at which he had always risen to begin his prayers. He was buried in the table tomb outside the church, leaving space for his brother John to be buried closer to the church door. The anniversary of the Feast of Nicholas Ferrar is now commemorated on 4th December though he actually died on the 2nd.

King Charles seeks refuge

In the Civil War Huntingdonshire was largely on the side of Parliament. As Royalists, therefore, the Ferrars found it safer to leave home, spending two years in Holland and returning to Little Gidding in late 1645 or early 1646. Within months, as King Charles secretly made his way north from Oxford to the Scots, he sought refuge on 2 May 1646 at Little Gidding (which he had previously visited in the spring of 1642). John Ferrar feared, however, that his house was no safe shelter for the king and led him to a safer bed at nearby Coppingford Lodge.

After the king’s visit the Ferrars lived quietly at Little Gidding until a flu epidemic in the autumn of 1657 carried off both John and his sister Susanna Collet. John’s descendants continued to live at the manor until the mid-18th century when the immediate male line died out and the manor was sold, the manor house being demolished in the early 19th century.

The Ferrar household was an example of a godly family, neither unique nor monastic, but firmly committed to the established Church of England and its Prayer Book and determined to follow Christ’s commands to forswear worldliness and devote themselves to God’s service. Their pattern of life placed them in a middle way that was neither Roman Catholicism, which founds its authority not only on scripture but also on church tradition, nor Genevan Protestantism, with its dependence only on scripture. The church at Little Gidding, with its reading desk and pulpit carefully placed at equal heights on either side of the church, expressed their vision of an appropriate balance of liturgy and preaching, a balance of tradition and scripture, interpreted by reason, that remains the heritage of the present Church of England.

Alleged ransacking of Little Gidding Church 1646

Brass font bowl thought to have been locally made in the Ferrar’s time. Read more

Letter from John Ferrar

This letter was transcribed by Bernard Blackstone in ‘The Ferrar papers’ and is given here: in John’s handwriting and the transcription.

“…the present sad and turbulent condition…a general deluge of consumptions of estates fell upon the whole land for our great sins…this last judgment of God an universal and unheard of punishment fell upon all for all had sinned; and in our particular estate we were scourged…we were fain to submit to a long sequestration for then the wars raged horribly but that was not all: to save our consciences from what was imposed that that might not ruin also we rather resolved to leave our native country and so I took you and my VF (Virginia) and went beyond sea…there being so many open wide throats gaping to devour Little Gidding.”

The Ferrar Papers, edited by B. Blackstone. Cambridge, University Press, 1938

In it John refers to his having left Gidding and gone overseas to Holland. John’s wife Bathsheba did not go with her family to Holland but stayed with relatives in Essex and returned to Gidding to collect the rents during their absence. The estate was briefly sequestered during the Commonwealth, and perhaps some deterioration came about as a consequence of neglect, but there is no mention of deliberate destruction, nor of the font being thrown into the pond. Indeed when the font was examined and restored by metallurgists at English Heritage in 1993 no evidence of immersion in water was found.

Peckard also alleges that the church organ was torn down and made into a fire upon which sheep were roasted: there is no evidence that there was an organ in the church, although there was certainly one in the Manor House.

Possible sources for the allegations:

The narrative given by Muir and White in their ‘Materials for the life of Nicholas Ferrar’ includes the notes written by John Ferrar for the eventual writing up of this life by an unidentified Historian. John Ferrar describes the scene at Nicholas’ deathbed when Nicholas commanded that his books be gathered together and burned on the place he had marked for his grave, and ‘a great smoke and bonfire and flame they made. And it being upon a hill, the towns round about and men in the fields came running up to the house, supposing some great fire had happened at Little Gidding….in a few days, it was by rumour spread all the country over at market towns that Mr Nicholas Ferrar lay a-dying, but he could not die till he had burned all his conjuring books and made a great fire of them upon the grave that he would be buried in.’ (p110 para 185)

Later, referring to the pamphlet The Arminian Nunnery published four years after Nicholas’ death (1641), and its allegations of Catholic practices, John writes that ‘although it was most easy to have been confuted’…’soldiers then raised, that came out of Essex to pass towards the north way to Gidding, intelligence was given them at Gidding, from good hands, that these books was given to many of them, and that they were hired and animated…to have offered violence to the family and house. But God Almighty, in his special providence, did turn away their fury at that time and it then passed over.’ (p111 para 187)

Muir, LR and White, JA editors. Proceedings of the Leeds Philosophical and Literary Society, Literary and Historical Section, Vol. XXIV, Part IV, pp. 263 – 428, December 1996

Nicholas Ferrar chapel at the church of the Good Shepherd, Arbury in Cambridge

A new church was built in the developing estate of Arbury in Cambridge, beginning in 1957. It was completed in 1964, under the guidance of members of the Oratory of the Good Shepherd (which was founded in Little Gidding church in 1913). The church was dedicated to the Good Shepherd, and as a memorial to Nicholas Ferrar, with the inclusion of the memorial chapel and statue of Nicholas Ferrar.

From a history of the church by its founder, the Superior of the OGS George Tibbats:

“This dedication is a permanent reminder that the parish came into being when the parish of Saint Luke’s and therefore the new estate was in the hands of brethren of the Oratory of the Good Shepherd.”